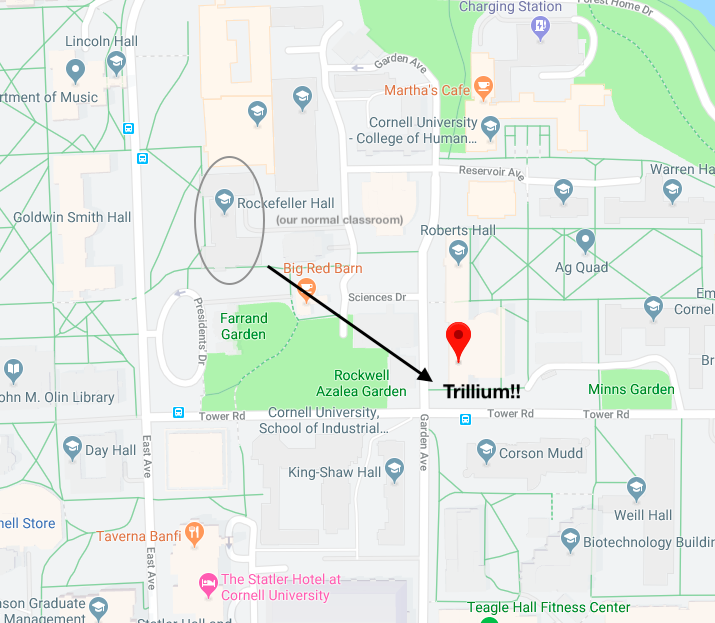

Reminder that we are meeting at Trillium (in Kennedy Hall) at 8:15 this morning. Get your coffee and omelets and then get ready to talk about the rhetoric of fact-checking.

On the rhetoric of fact-checking

Cloud’s third chapter is part of a larger book about how truth and reality is established in US political culture. Let’s spend some of our time trying to understand it by looking more closely at moments in the text. For each moment we discuss, let’s try to understand what’s happening at that point in the chapter and why it is important. We might look at:

- areas of the text did you marked up.

- areas where Cloud is posing questions.

- key terms or words you looked up or wanted to spend more time trying to understand.

- places where the text is making claims versus using evidence

- areas of the text that gives us context

- moments when the author is addressing or anticipating perspectives different from their own.

Frames of post-truth

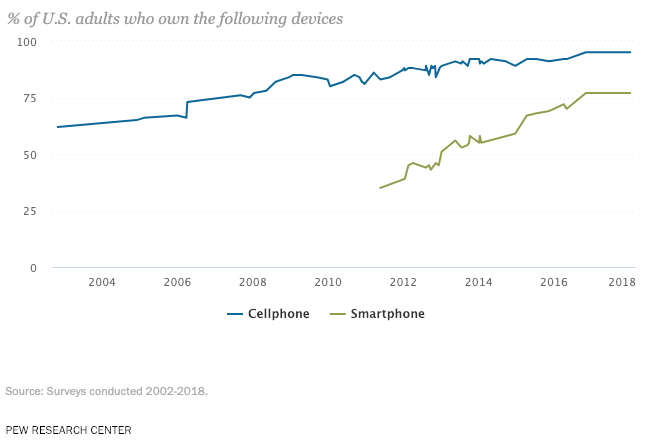

As you’ve no doubt learned by now, we live at time when claims to facts and truth are hyper-mediated; that is, for most of us living in the western world, our understanding of reality is filtered by hourly engagement with digitally-networked technologies. More than 3 out of every 4 adults in the United States, for example, own a smartphone — a figure that has doubled in only 7 years.

While Google has been around since 1998, 15 years ago Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram did not exist (at least publically). These brief examples don’t account for the development of broadband networks, the central role of sharing economies, nor rise of surveillance technologies. In other words, the introduction of these devices and programs have radically changed the nature of our everyday reality.

In this next unit you’ll be introduced to several frameworks for better understanding how this reality is arranged, filtered, and projected. Frameworks are helpful in that they provide readers with broader perspectives — lenses — for understanding why things seem to be they way they are. Our lenses for this purpose will include politics, economics, culture, psychology, and technology. We will read and discuss each of these frameworks in order to try to see how they affect the ways we access, assess, and subsequently produce truth.

While we will attempt to read through these lens separately, often they overlap. For example, when we look at economics of post-truth, we will hear a podcast about two entrepreneurs who exploited vulnerabilities in Facebook’s technology in order to make money; however, in their pursuit of economic success, the podcast producers argue that the entrepreneurs also contributed to vitriolic political polarization in US culture. Such overlap will be useful in the next unit when you begin to fact-check various claims on the web, tracing their roots back to some of these frameworks.

Methods of Annotation

The work of this unit thus entails reading and looking at examples. As such, you will be graded on your ability to make your process of reading visible to me and others through annotations. We will experiment with three different methods or approaches to annotation as a result:

Marginal — This print-based, dialogic approach involves going beyond highlighting to point out and trace the major features of a text (argument, evidence, examples, etc.) and to converse with it.

Holistic — This broader annotation strategy requires readers to keep a separate place for notes that summarizes the text, pulls relevant quotations, and maps keywords and sources.

Social — This method involves using web annotation tools (we will use hypothes.is) to have a conversation about web texts with other users.

Homework for tomorrow (Thursday)

- Read the Meta-Reading Checklist and apply it by

- annotating chapters from Roberts-Miller’s book: the short introduction, Chapter III (“What Demagoguery Is”) and IV (“How Demagoguery Works”).